A selection of Steven Levingston’s pieces on drama.

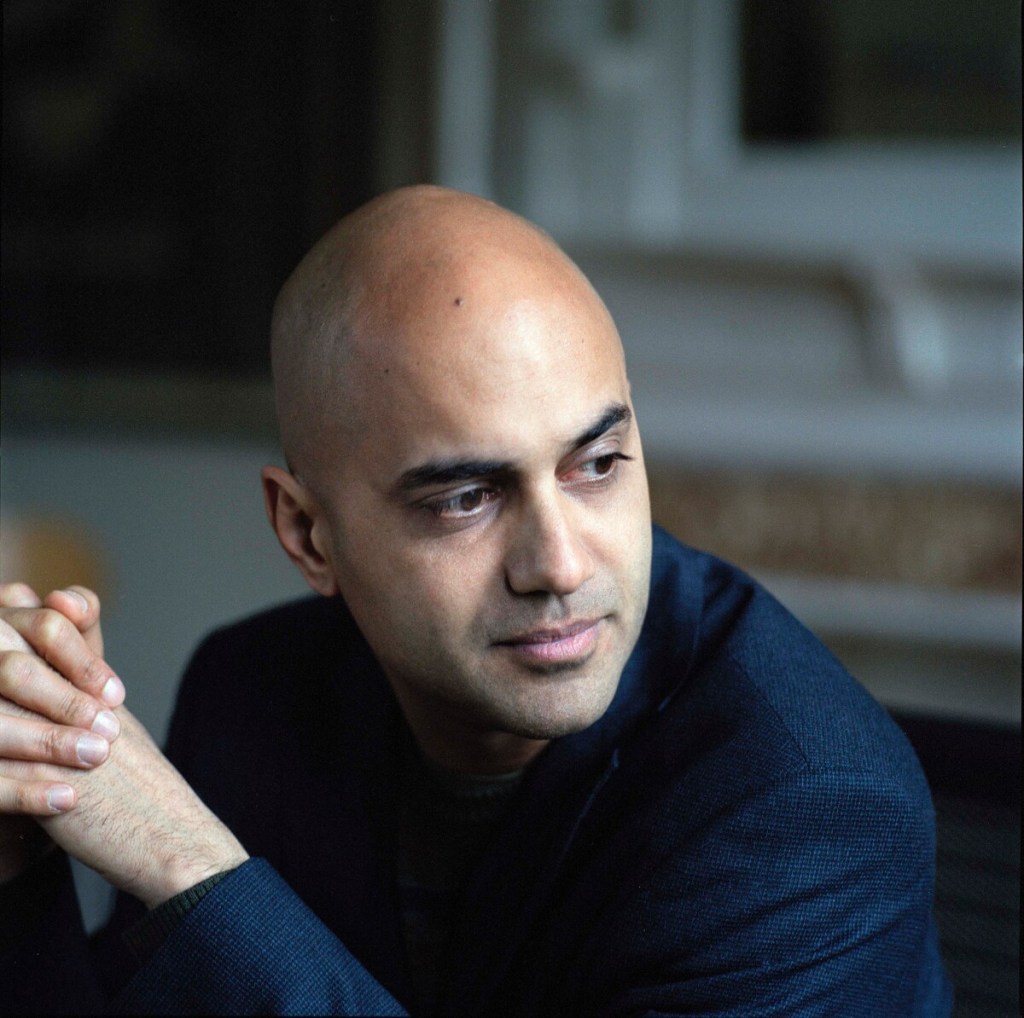

Ayad Akhtar: On Muslim identity, and life in America

(WP 7/19/2014)

To appreciate the relevance of playwright Ayad Akhtar’s work, you need look no further than two eerie coincidences that shadowed his debut drama, “Disgraced.” The play, which portrays the downfall of a Muslim American lawyer, won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 2013. The day the award was announced, two Muslims deposited pressure-cooker bombs near the finish line of the Boston marathon. A second grisly coincidence came a few weeks later. On the day “Disgraced” opened in London two Muslims murdered and tried to behead a British soldier on a busy street in what one said was revenge for the British army’s killing of Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nobody linked these attacks to Akhtar’s play, but they were nonetheless chilling reminders of the violence that hovers at the edges of the territory he explores. “The work I’m doing is in direct dialogue with what’s happening in the Muslim world,” he said recently over dinner in New York.

Read more here.

Q&A with Ayad Akhtar, the Pulitzer Prize winner in drama

(WP 4/19/2013)

Ayad Akhtar, who received the Pulitzer Prize in drama last week, is a man of many talents and daring insights. As an actor, screenwriter, novelist and playwright, he challenges Americans to question their assumptions about race and religion.

Born in New York City to Pakistani immigrants and raised in Milwaukee, Akhtar played an enigmatic Pakistani engineering student who turns from secularism to terrorism in the film “The War Within,” which he also co-wrote.

Read more here.

My drama: Getting a new play staged is all comedy and tragedy

(WP Magazine 4/5/2013)

About three years ago I did something that only a puffed-up fool would do: I wrote a play. For three weeks I was maniacal about it, and when I dropped the final curtain I nodded my head knowingly — this baby was a winner: All I had to do was get the script into the right hands, and before I could belt out, “There’s no business like show business,” audiences would be filling the seats, laughing and applauding riotously in the dark.

Thus began my tale of what Eugene O’Neill might call a lunatic’s pipe dream, a story of innocence, hope and crushing neglect. But it’s not my story alone. You need only read a day’s worth of the yearnings on LinkedIn’s playwriting group, scan the entry rules for hundreds of play competitions, or study the stiff-armed guidelines for submissions to regional theaters to realize that other pipe-dreaming playwrights-to-be are having their own egos stomped. Yet, we keep coming back for more, knowing full well that the odds of getting a play produced are about the same as getting killed by a falling coconut (that’s one in 250 million) — or at least it feels that way.

Read more here.

‘My Fair Lady’ replacement shines at Arena Stage in an unforgettable evening

(WP 1/6/2013)

It was looking awfully bleak for the Saturday evening performance of “My Fair Lady” when Artistic Director Molly Smith walked onstage surrounded by her cast to deliver some grim news.

She informed the nearly full house that flu had laid low several cast members, including Manna Nichols, who played the lead role of Eliza Doolittle.

To have an understudy step in is usually a disappointment for an audience that arrives expecting to see the stars. In this case, even Nichols’s replacement, Erin Driscoll, was absent: She had lost her voice.

Read more here.

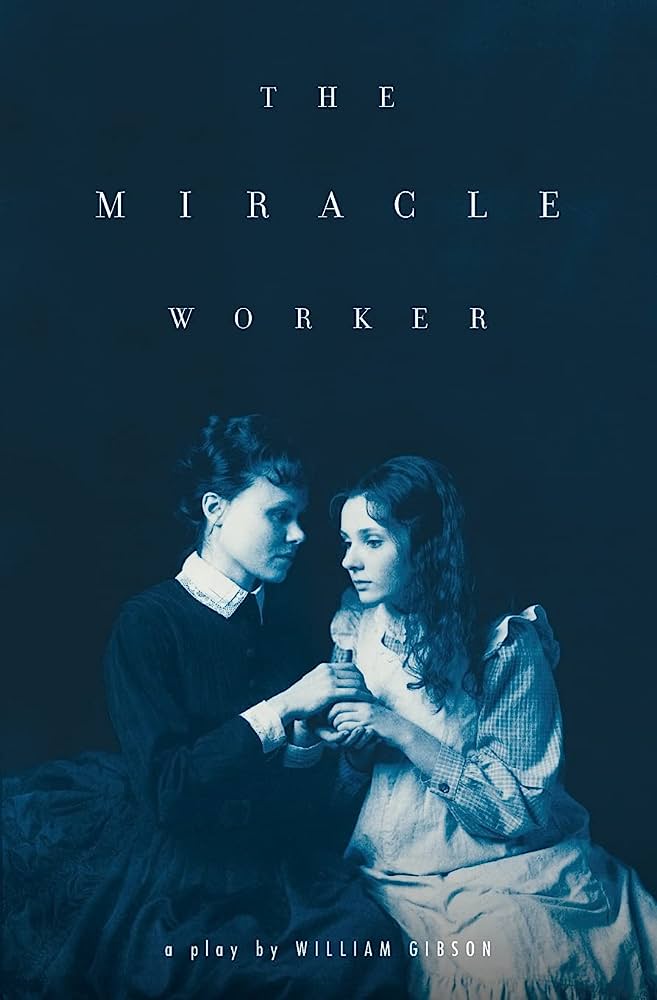

Why plays make the perfect summer reading

(WP 6/18/2011)

Rummaging in the basement a few weeks ago, I came upon a copy of William Gibson’s play “The Miracle Worker” in a 40-cent, Bantam paperback edition from 1962, its pages the color of a Daguerreotype. I started reading and couldn’t stop. This 1960 Tony Award-winner is the story of Annie Sullivan, who overcomes daunting odds to teach the deaf, blind, mute Helen Keller to communicate. As a play-reading experience, it is near-perfect. The dialogue gives vivid shape to stubborn Annie and each member of Helen’s tortured family. You won’t find any thriller more gripping, more packed with a daisy chain of dramatic crises.

But read a play? What a nutty idea! Plays aren’t meant to be read, they’re to be seen and heard. Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Donald Margulies understands this: He writes not for the page but for the stage. His plays, he told me, are blueprints for actors and directors, incomplete until they’re performed. Tennessee Williams knew this, too. He tested out his new plays by reading them aloud to friends. Thornton Wilder perhaps put it best. He said that while fiction, painting and sculpture can be appreciated in solitude, “a play presupposes a crowd.”

Read more here.